The “Gold Standard” for Autistic Children

So many Autistic people explain how and why ABA is abusive and harmful, yet many professionals continue to push it.

I have heard this line so many times.

“They told me ABA therapy was the ‘gold standard’ for Autism.”

They, meaning the professionals, need to explain exactly what they mean by that, because gold standard is subjective, and will mean different things to different people.

The “gold standard” that ABA is known for is forcing Autistic children to behave as neurotypical as possible.

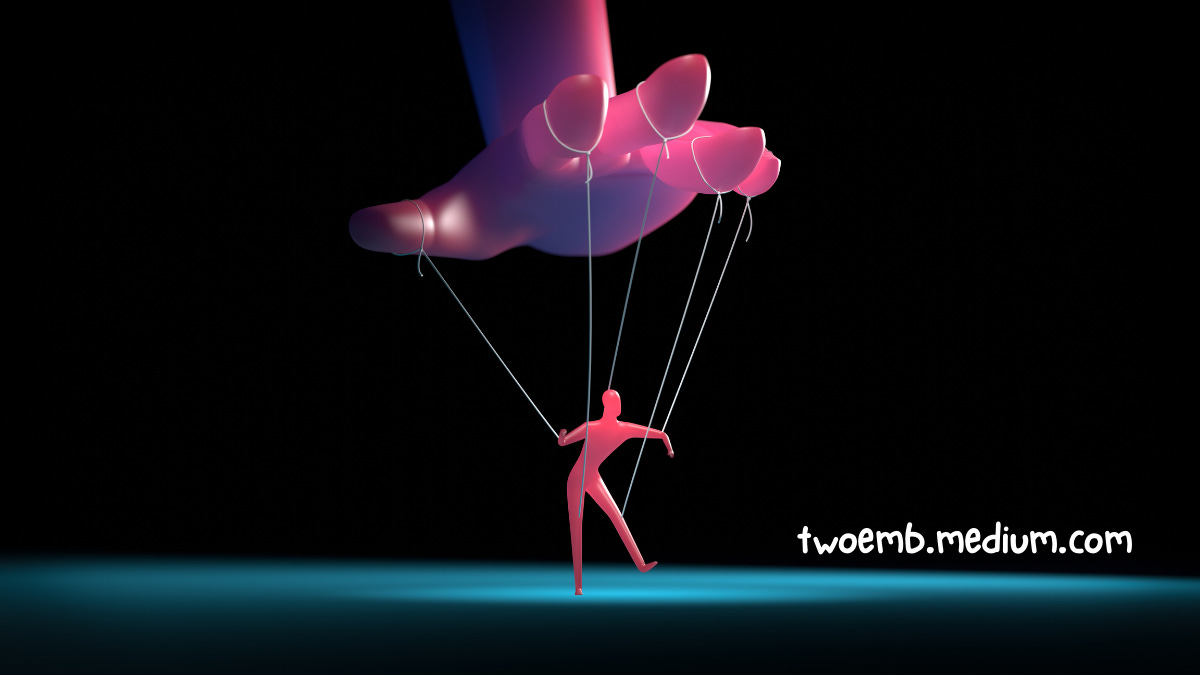

ABA uses punishments and rewards to train human beings like puppies under the guise of teaching them the “skills” they will need to succeed in life.

The problem with the way this is done is that it’s entirely centred around neurotypical adults and what they want from the child and for the child.

These approaches are harmful because they only focus on surface behaviours and modifying them to fit some — often unfair and unrealistic — set of expectations, without respect or regard for the Autistic human being.

For example, ABA therapy often seeks to stop Autistic children from stimming. Stimming is self-stimulatory behaviour and is often a way that Autistic people regulate emotions. It can be calming, it can be enjoyable, and sometimes it signals to others that something is wrong.

Under ABA, which stands for applied behaviour analysis, we would punish the stimming behaviour and reward an alternative behaviour (one the neurotypical adults deem “acceptable”), in order to reduce the former and increase the latter.

The type of punishment can vary depending on the therapists, the people in the environment, and the person applying the so-called intervention. This can be removal of something the person enjoys (called negative punishment) or doing something to them they dislike (called “positive” punishment, because something is being added, rather than taken away).

One website, which I will not link to as I believe it is harmful, states the following:

“Through the use of clear definitions for behavior and systematic delivery of interventions, reliable relationships between interventions and behavior can be established.”

The word interventions means punishments and rewards. So the therapist, parent, or teacher consistently follows specific unwanted behaviours with punishments and specific desired behaviours with rewards in order for the Autistic person to make the connection and perform the desired behaviours more often.

This is exactly like puppy training.

My child is not a puppy. Autistic human beings are not puppies.

Human behaviour is never that simple

It’s also ridiculously reductionist. All human beings have many complex reasons for why they perform certain behaviours, and explaining what maintains a behaviour cannot be boiled down to a single reinforcer.

We all do things in life we know aren’t good for us because they’re rewarding or pleasurable in the moment. We also do things, or avoid doing things, in the present even when we know we might pay for them later.

“That’s a future-me problem.”

Our behaviour in one moment is also not a direct result of the preceding moment alone. If I get angry at my husband when he asks me to pass the salt, I’m probably not annoyed with him for making that simple request. It’s more likely I’m annoyed at something else he did earlier, or maybe I’m mad at something and someone else entirely.

Perhaps I’ve had pent up frustration boiling inside of me all day, and it finally comes out where I feel safe. Similarly, when a child lashes out or exhibits a behaviour the adults don’t like, it’s highly probable a number of precipitating events led up to the moment in question.

ABA focuses on the needs of NT adults

ABA therapy focuses primarily on the needs of the neurotypical adults in the child’s life and not on the child’s needs.

“Behaviour management is about the adults.”

— Dr. Lori Desautels

Many people justify the dehumanizing treatment by claiming that Autistic children need to learn certain skills in order to be “functional” and successful in society.

However, the method by which they do this requires Autistic individuals to suppress and ignore the very essence of who we are, and to deny our own needs for the sake of those around us.

Stimming is important to help me feel better, but it makes some NT people uncomfortable. I have to mask or suppress that need even though it hurts no one and is beneficial to me.

Instead of looking beneath overt behaviours to figure out why a person may or may not be doing something, ABA simply manipulates both the environment and the child, with the end goal of compliance.

“Although adult-imposed consequences might be effective at modifying a student’s behaviours, they don’t solve the problems that are causing those behaviours.”

— Dr. Ross Greene

When you ass-um-e…

If a child is asked to perform a task at school and is unable to do so in the moment because of sensory issues, anxiety, stress, or they just don’t bloody want to, those factors are completely ignored.

When a child “acts out”, adults often speak about their behaviour as though it were intentional.

“The concept of misbehaviour is fundamentally tied to those of volition, choice, and awareness.” — Siegel & Bryson

Rather than stopping and offering the child opportunities to communicate their needs, and then working with that child to meet those needs, ABA practitioners make a demand and then use the threat of consequence to get their way.

Even if this is done in the “new” ABA way, with a smile and a gentle tone, or pretty stickers on a chart, it is still the same shit in a different pile. Perhaps with a pretty bow on top. It may look a bit nicer, but it still stinks.

A lot of “misbehaviour” is actually stress behaviour, especially in neurodivergent children who are constantly misunderstood and forced to try to fit their divergent square-peg selves into a neurotypical-centric, round-hole world.

“Too often, caregivers, teachers, providers, and parents assume that a child is acting deliberately, when in fact a behaviour is actually a stress response.”

— Dr. Mona Delahooke

What if the child is hungry or thirsty? The room is too loud, too bright, too hot? Maybe the pencil they’re being asked to use doesn’t have the rubber grip they usually use, and it’s uncomfortable to write without it. Who knows? Certainly not the ABA practitioner because they didn’t bother to ask.

“But it’s done wonders for my child!”

Has it, though?

“ABA infringes on the autonomy of children.”

— Wilkenfeld & McCarthy

Research conducted in 2018 found that camouflaging (aka masking) and unmet support needs were the two greatest risk factors for suicidality in Autistic individuals.

This encapsulates the entire essence of ABA: camouflage your autism so that you are more convenient to the neurotypical majority and ignore your own needs in order to do what is expected of you.

Oh yes, and do this simply because of arbitrary, often meaningless, social norms.

Camouflage your autism so that you are more convenient to the neurotypical majority and ignore your own needs in order to do what is expected of you.

Priorities

Do you really want to spend a significant portion of someone’s childhood communicating to them that they are not good enough the way they are; forcing them to go to therapies that make them miserable, so that they’re “easier” to manage at home and school?

“Is ‘normal’ best achieved by holing up in the offices of therapists, in special classrooms, in isolated exercises, in simulated living, while everyday ‘normal’ happens casually on the other side of the wall? And is ‘normal’ superior to who the child inherently is?”

— Beth Kephart

What if, instead, we show all children that they’re awesome for being their unique selves, and played to their strengths? What if we stopped giving a shit about social norms, and instead prioritized children’s needs over societal expectations?

What if we stopped giving a shit about social norms, and instead put children’s needs over societal expectations?

Certainly, we still need to teach and guide our children, that’s part of parenting.

An even more important part of parenting is being the person in your child’s life who always loves and accepts them for exactly who they are, and protects them from harm, no matter what.

That’s the gold standard.

© Jillian Enright, Neurodiversity MB

Related articles

Children Are Cute, But They’re Not Puppies

Behaviour Management Programs are Harmful & Ableist

Stop Recommending Behaviour Therapies

Ways to support my work

You can leave a “tip” on Ko-Fi at https://Ko-Fi.com/NeurodiversityMB

Become a paid subscriber to my Substack publication

Check out my online store at https://NeurodiversityMB.ca/shop

Read and share my articles from twoemb.medium.com

You can also follow me on facebook, and find all my links on LinkTree

Learn more

References

Autistic Science Person. (2021). “Why ABA Therapy Is Harmful to Autistic People.” Autistic Science Person, Autistic Science Person, 4 Nov. 2021. https://autisticscienceperson.com/why-aba-therapy-is-harmful-to-autistic-people

Cassidy, S., Bradley, L., Shaw, R., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular autism, 9, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4

Delahooke, M. (2019). Beyond Behaviors: using brain science and compassion to understand and solve children’s behavioral challenges. PESI Publishing.

Desautels, L. (2020). Connections Over Compliance: Rewiring our perceptions of discipline. Wyatt-MacKenzie Publishing.

Greene, R. W. (2021). Lost & Found: Unlocking collaboration and compassion to help our most vulnerable, misunderstood students, and all the rest. (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Kephart, B. (1998). A Slant of Sun: One Child’s Courage. W. W. Norton.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2020). The power of showing up: How parental presence shapes who our kids become and how their brains get wired. Ballantine Books.

Stixrud, W. & Johnson, N. (2019). The Self-Driven Child: The science and sense of giving your kids more control over their lives. Penguin Books.

Wilkenfeld, D.A., & McCarthy, A.M. (2020). Ethical Concerns with Applied Behavior Analysis for Autism Spectrum “Disorder”. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 30(1), 31–69. https://doi.org/10.1353/ken.2020.0000