If Anyone Wants Me, I’ll Be in My Room

Bart and Blue Jeans as Revolutionary Counter-Culture (Part 2)

Please note

I originally wrote this as an analytical reading synthesis for a rhetoric and communications class. I have edited it and broken it into two parts to make it easier to read. This is part two of two. If you missed part one, I recommend reading it first. I hope you enjoy!

“If anyone wants me, I’ll be in my room”

As I explained in part one (with help from John Street), to radical elitists, popular culture is an expression of “forces which seek to prevent change, or to promote changes that do not benefit the majority of people”.

Art critic John Berger asserts, “The art of any period tends to serve the ideological interests of the ruling class”. Like Berger, radical elites believe radicalism and populism are mutually exclusive. Street writes that for these elitists, “radicalism is eliminated in the process of commercialization”.

This issue was demonstrated in the Decoder podcast when Paskin described how Bart Simpson’s image was used in pro-war propaganda during America’s illegal invasion of Iraq. Various bootlegged T-shirts showed Bart throttling Saddam Hussein, peeing on a map of Iraq, and standing in a gas mask saying “go ahead Hussein, have a cow”. This is an example of Street’s description of how culture is “manufactured to reproduce the logic and rhythms of capitalism”, and is intentionally designed “to elicit set responses”.

My favourite Simpsons character, Lisa Simpson, is a great example of a radical elitist. Highly intelligent and principled, Lisa often takes on large and important social issues. However, there are times when Lisa appears to take on an issue merely for the sake of being contrary or to resist a social norm, regardless of her actual position on the issue.

For example, in the episode Bart Star, Lisa declares she would like to join the football team. When it is revealed there are already girls on the team, she instead rails against a sport that would use a pig’s skin to make its ball. Upon learning that not only is the football synthetic, the proceeds from its purchase went to charity, Lisa is at a loss for words and runs away.

While I agree that culture can and does often uphold existing problematic social norms, a refusal to see how culture has the potential at times be revolutionary and subversive can lead to a persistent battle against popular culture without adequate critical thought or analysis — much like the radical elitists.

On the Decoder podcast, Paskin gives examples of when Lisa is truly radical in the episode entitled The Springfield Connection. When Lisa’s mother, Marge Simpson, tells the family she has been hired as a police offer, Lisa’s response is to ask, “Aren’t the police the protective force that maintains the status quo for the wealthy elite? Don’t you think we ought to attack the roots of social problems instead of jamming people into overcrowded prisons?”

This is an example of the radical elite philosophy holding true. The police force, like art, “justifies most other forms of authority”, and exploits that authority to “glorify the social system and its priorities”. Go Lisa.

In a wonderful coincidence, The Springfield Connection is the same episode in which Homer discovers a counterfeit blue jean ring running out of his “car hole”.

“Eat my [jean] shorts”

Last but not least, radical populists argue “we can learn at least as much, if not more, about resistances to the dominant ideology from studying popular everyday tactics” as we can from “theorizing and analyzing the strategic mechanisms of power”. Here Street draws significantly from philosopher and historian John Fiske. In his book, Understanding Popular Culture, Fiske compares social resistance with the “distressed” style of blue jeans.

He writes, “If today’s jeans are to express oppositional meanings, or even to gesture toward such social resistance, they need to be disfigured in some way… disfiguring them becomes a way of distancing oneself from those values”. By wearing the jeans, however, we are not completely rejecting popular culture because we are still, in fact, wearing the jeans. Instead, we are situating ourselves — and, by extension, an element of popular culture — “firmly within a model of power”. In so doing, we reveal the contradictions inherent in a culture industry whose interests are “in direct opposition” to ours.

This is where the star of our episode, Bart Simpson, makes his fashionably late entrance. Bart is the embodiment of radical populism. He’s a rebel (often without a cause), he sometimes offers very clever and subversive social commentary, and most certainly uses his place in popular culture to resist or challenge dominant social values and ideologies. An illustrative example Willa Paskin uses in Bart Simpson Mania is the Simpsons versus the Huxtables controversy of 1992.

On February 20 of that year, Fox strategically moved The Simpsons into a different time slot so it would be in direct competition with The Cosby Show. In Bart Simpson versus Cliff Huxtable, it was Bart who emerged victorious. As Willa Paskin explains, Bart and The Simpsons weren’t merely subversive because of Bart’s rude humour and disrespectful behaviour. The Simpsons were a symbolic stand-in for the American family, and with Bart’s help, they were pushing back against phony American idealism.

Conclusion

The prescriptivist view of popular culture is one logical fallacy utilized by conservative elitists. As O’Brien and Szeman explain in their book Popular Culture : A user’s guide, “The meanings we take from cultural texts come from a combination of convention, individual subjectivity, and experience”.

Inferring a direct causal relationship between the media we consume and our subsequent behaviour is an over-simplistic, narrow view of human psychology and behaviour. If what we watched, heard, and read could so easily and directly manipulate our behaviour, I would have been riding around on a skateboard saying “eat my shorts” and “don’t have a cow, man” for an entire decade of my life.

To put it less subjectively, O’Brien and Szeman conclude that this type of prescriptivism “seriously underrates the complexity of the processes by which human beings read and respond to the world around them”.

Street comes to similar conclusions, highlighting the multi-faceted systemic factors at play when determining what is “good” and what is not in popular culture. The subjective and dynamic standards by which we made judgements are “maintained by complex systems of legitimation and authority” and are “constantly vulnerable to erosion and reconstruction”.

Street urges us to consider the ways in which “popular culture engages with politics”, understanding popular culture as an “organizing force”, one which helps its consumers “articulate feelings” in the way it gives them form. He reminds the reader that politics and popular culture influence one another, while also appreciating how it can provide modes of expression for sentiments we may otherwise be unable to convey.

Personally, I think a critical balance between radical elitism and radical populism is important. While I do believe popular culture can be a highly effective means of expressing critical social commentary, I also agree that it is very quickly subsumed by capitalism, and reformatted for its own purposes — just as certain bootlegged Bart merchandise was used as a propaganda tool, to exploit Bart’s popularity in order to spread pro-war messaging.

Perhaps when Maggie finally learns to talk, she’ll be the balancing presence in the Simpsons family. Even better, maybe she’ll follow in the footsteps of Adil Hoxha and become a member of the Springfield Communist Party one day.

We can hope.

© Jillian Enright, Neurodiversity MB

Related articles

Bart and Blue Jeans as Revolutionary Counter-Culture

“Look Over There!”: The Politics of Distraction

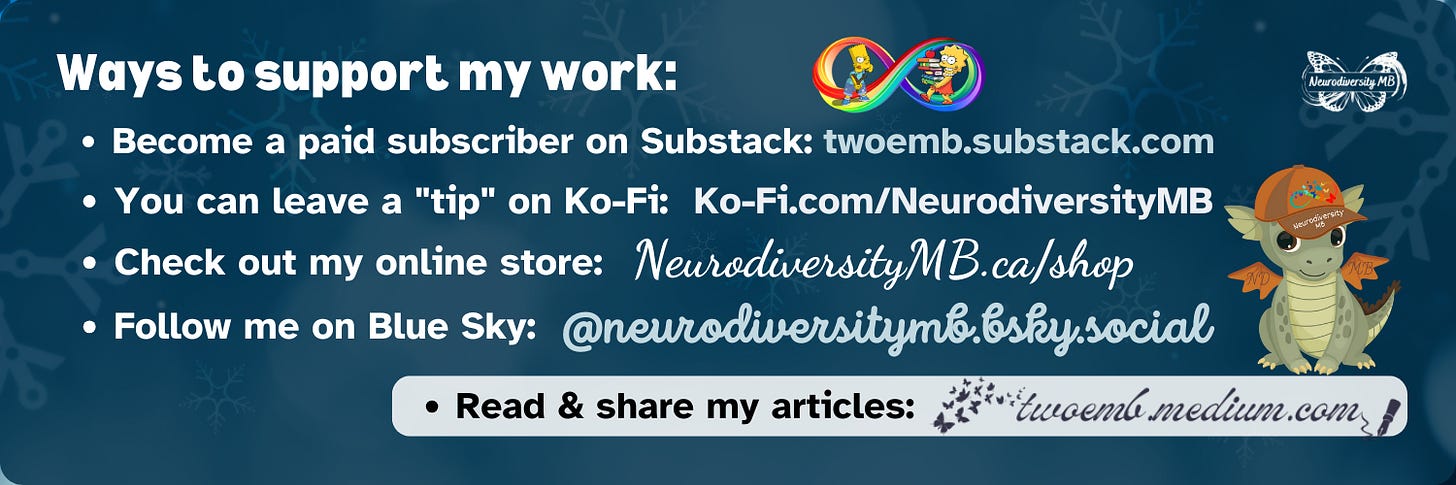

Ways to support my work

You can leave a “tip” on Ko-Fi at https://Ko-Fi.com/NeurodiversityMB

Become a paid subscriber to my Substack publication

Check out my online store at https://NeurodiversityMB.ca/shop

Read and share my articles from twoemb.medium.com

You can also follow me on facebook & Blue Sky, and find all my links on LinkTree

Learn more

The Populism to Fascism Pipeline

Populism, Panic, and the Politics of Fear

Pierre Poilievre’s Populism to Baby-Fascism Pipeline

References

Berger, John. (1972). Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books.

Evans, Greg. (2021, February 21). A deep dive into Birch Barlow, the ‘Rush Limbaugh’ of The Simpsons. Indy100.

Fiske, John. (2010). Understanding Popular Culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Groening, Matt. (1997, November 9). Bart Star (S9, E6). The Simpsons. Fox Television.

Groening, Matt. (1995, May 7). The Springfield Connection (S6, E23). The Simpsons. Fox Television.

Groening, Matt. (1987, April 19). Good Night (S1, E1). The Simpsons. The Tracey Ullman Show. Fox Television.

Kenneth. [Inside Ken’s Mind]. (2015, August 13). Presidents in Parody: Two Bad Neighbours. [Potus Geeks Blog].

Malinowski, E. (2012, February 20). The Making Of “Homer At The Bat,” The Episode That Conquered Prime Time 20 Years Ago Tonight. DeadSpin.

Müller, J.-W. (2015). Parsing Populism: Who is and who is not a populist these days? Juncture, 22(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2050-5876.2015.00842.x

O’Brien, S., & Szeman, I. (2018). Popular Culture : A user’s guide (4th ed.). Nelson.

Paskin, Willa. (2019, October 7). Bart Simpson Mania: Who’s afraid of Bart Simpson? Slate : Decoder Ring. https://slate.com/podcasts/decoder-ring/2019/10/decoder-ring-bart-simpson-culture-wars-george-h-w-bush. Slate.

Robin, Corey. (2018). The Reactionary Mind (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Street, John. (1997). Political Theories of Culture. In Politics and popular culture (pp. 147–167). Temple University Press.

Stoddard, Catherine. (2025, January 31). How ‘The Simpsons’ survived these early controversies. Live Fox Now News.

"My favourite Simpsons character, Lisa Simpson, is a great example of a radical elitist. Highly intelligent and principled, Lisa often takes on large and important social issues. However, there are times when Lisa appears to take on an issue merely for the sake of being contrary or to resist a social norm, regardless of her actual position on the issue."

We think alike. She's mine as well, and a leading contender for my favorite fictional character- period.