Asperger Didn’t “Discover” Autism

A woman named Dr. Grunya Sukhareva identified and published her own research on autism in 1925

Dr. Grunya Sukhareva

Dr. Hans Asperger and Dr. Leo Kanner were not the first to identify, study, research, or publish articles about autism. Dr. Grunya Sukhareva, a renowned Russian child and adolescent psychiatrist, published articles in 1925 and 1926 which contain the first academic description of autism in young male and female patients. Being a woman in the 1920s — however well-qualified and educated — likely had much to do with Asperger’s (and other’s) willingness to disregard, and then take credit, for her work.

Sukhareva’s work not only provided a clinical description of what we now recognize as autism before male colleagues Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger, her research also delved into the existence of gender differences in Autistic presentation.

Turns out Asperger didn’t just assist the German nazis in carrying out their eugenics and euthanasia programs. He also did this (in part) by stealing, twisting, misrepresenting, and misusing Dr. Grunya Sukhareva’s work for his own personal and professional gain.

Dr. Grunya Sukhareva described the following “impairments” in what was then called a “schizoid personality disorder of childhood”:

psychomotor impairment: awkwardness, angular movements, bipolarity between excitation and lethargy, automatism, and stereotypies (repetitive movements);

emotional impairment: weak affective attachment to others, lack of unity of emotional experiences; and

a difference in associative work and thinking: unusual associations, inclination to abstract thinking, automated thoughts, rigidity/inflexible thinking.

I’ll briefly touch upon each and give a more modern description of what they generally could mean.

Psychomotor impairment

Motor and movement disorders are more common in Autistic people than they are in the general population. We often struggle with proprioception, the awareness of our body’s location in space and in relation to things around us (which is why I tend to bump into stationary objects…).

A lot of Autistics also have difficulty with fine motor control, some of which can be “sub-clinical” (which just means it doesn’t impact us enough to warrant a formal diagnosis, but it still exists), but for some people it can lead to conditions such as Apraxia and Dysrpaxia.

Autistics are also at higher risk for hypermobility disorders which can, among other things, cause difficulty with coordination and significantly increased risk of joint pain and injuries, such as dislocation.

Emotional impairment

This description of “weak affective attachment to others” is, of course, highly out-dated. We now understand that many Autistic people experience very intense levels of empathy, however we often experience, process, and express our emotions differently from allistic (non-autistic) people.

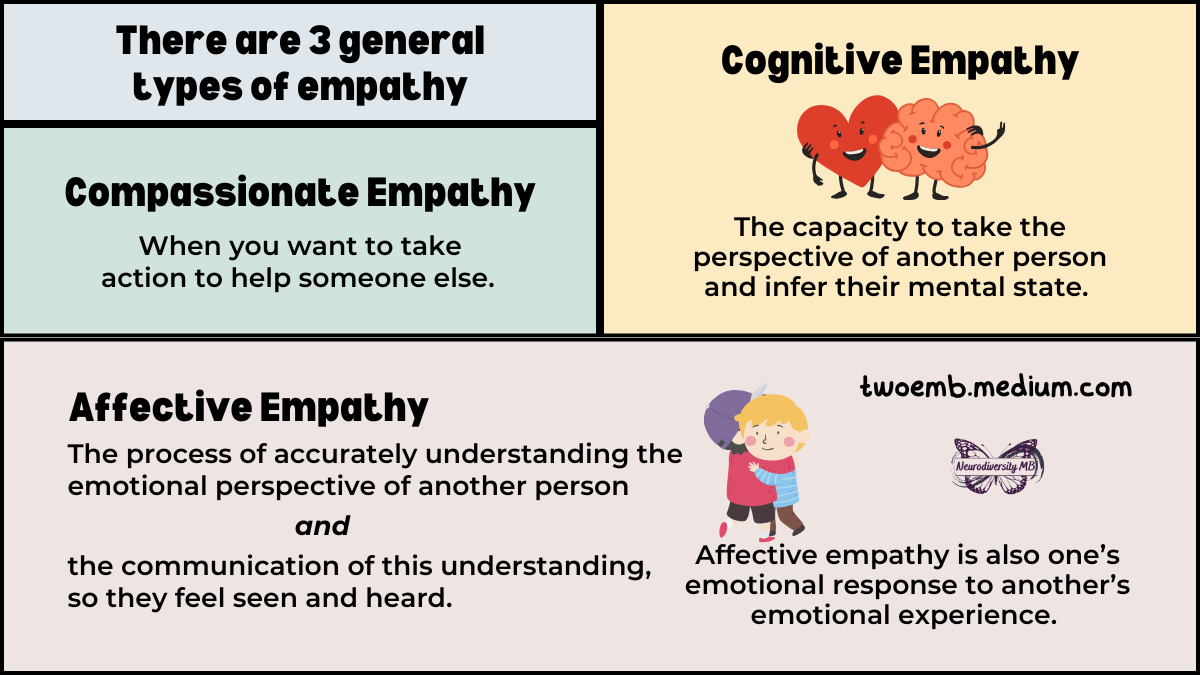

More commonly, Autistic people may struggle with cognitive empathy, but possess strong affective empathy. Affective empathy is the process of accurately understanding the emotional perspective of others, and effectively communicating this understanding, so others feel seen and heard.

We may still struggle with this because of our differences in processing and expressing our feelings, but this does not mean we lack the skill entirely, and in fact, some Autistics have it in spades.

Cognitive empathy is the capacity to take the perspective of another person and infer their mental state. Autistic people may struggle with this for any number of reasons.

One could be that we are socialized with predominately neurotypical cultural and social norms. What we’re told emotions are “supposed” to look and feel like may not line up with our lived experiences.

This makes it much more difficult for Autistics to identify and understand our own emotions (called alexithymia). This is a lack of information and self-knowledge, not a lack of emotions.

Just as neurodivergent folks tend to have spiky cognitive profiles and asynchronous development, we can also experience empathic disequilibrium, which is an imbalance between cognitive and affective empathy.

When we’re aware of someone’s distress, we may be strongly affected, experience significant concern, and want to help. We may not understand why they’re upset or what we can do to help, which may serve to intensify our emotional response. This is a cultural difference — a difference in communication and emotional support across neurotypes — not a lack of empathy.

Associative learning

“Associative work and thinking” refers to making connections between ideas or experiences to help us remember them, and cognitive rigidity describes an executive functioning challenge which causes difficulty adapting to change.

For example, if we learn and internalize a particular rule or social norm in a particular context, we may struggle to “unlearn” or adapt to changing expectations in different environments. We may have difficulty seeing shades of grey or being flexible once we’ve established a way of doing things that works for us.

That said, cognitive rigidity can also have surprising benefits. Autistic people (generally speaking, of course) tend to have more stable morals as a result of this inflexibility. We may be more ethically consistent and principled because we have internalized a value and will strongly resist ceding to external pressure.

Strong morals and justice sensitivity

This isn’t the case with everyone, of course, and certainly not all Autistic people embody this ethical consistency either. One such anomaly I spoke of recently is Elon Musk, an aspie supremacist and overt nazi. While he tells the world he has “aspergers” (an outdated label for more than 12 years), he behaves in absolutely horrendous, hateful, and harmful ways.

This gives the Autistic community a bad name and a bad reputation. It also gives his supporters an excuse to point to when Muskolini behaves badly: “it’s not his fault, it’s the autism!”

No.

Musk claims to have a higher-than-average intellect. While that is highly debatable, it is clear he is entirely capable of knowing the difference between right and wrong. Autism is not an excuse for bigotry, not from anyone, and especially not from someone with as much money, power, and influence as that fascist.

© Jillian Enright, Neurodiversity MB

Related articles

Elon Musk is an Aspie Supremacist

Naziism (Still) Influences Modern Psychology

Sometimes We Need to be Maladjusted

Ways to support my work

You can leave a “tip” on Ko-Fi at https://Ko-Fi.com/NeurodiversityMB

Become a paid subscriber to my Substack publication

Check out my online store at https://NeurodiversityMB.ca/shop

Read and share my articles from twoemb.medium.com

You can also follow me on facebook & Blue Sky, and find all my links on LinkTree

Learn more

Autistic People Are Not Unfeeling Robots

Everything You Never Wanted To Know About Executive Functions

References

Dell’Osso, L., & Carpita, B. (2023). What misdiagnoses do women with autism spectrum disorder receive in the DSM-5? CNS Spectrums, 28(3), 269–270. doi:10.1017/S1092852922000037

Dell’Osso, L., Toschi, D., Carpita, B., & Amatori, G. (2024). Female autism: Grunya Sukhareva’s pioneering description reinterpreted in light of DSM-5-TR and the concept of camouflaging. Italian Journal of Psychiatry, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.36180/2421-4469-2024-1

Sapey-Triomphe, L. A., Weilnhammer, V. A., & Wagemans, J. (2022). Associative learning under uncertainty in adults with autism: Intact learning of the cue-outcome contingency, but slower updating of priors. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 26(5), 1216–1228. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211045026

Shalev, I., & Uzefovsky, F. (2020). Empathic disequilibrium in two different measures of empathy predicts autism traits in neurotypical population. Molecular autism, 11(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-020-00362-1

Shebib, B. (2023). Choices: Interviewing and counselling skills for Canadians (8th ed.). Pearson Canada.

Simmonds, C., & Sukhareva, G. E. (2019). The first account of the syndrome Asperger described? Part 2: the girls. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(4), 549–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01371-z

Wolff, S. (1996). The first account of the syndrome Asperger described? : Translation of a paper entitled “Die schizoiden Psychopathien im Kindesalter by Dr. G. E. Ssucharewa; scientific assistant, which appeared in 1926 in the Monatsschrift für Psychiatrie und Neurologie 60:235–261. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 5(3), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00571671